Nothing in Texas is more iconic than Longhorn cattle. The Longhorn even has its own folklore. In Native American cultures the Longhorn represents a symbol of good luck and spiritual guidance. While in Spanish culture, the Longhorn represents power, resilience, and strength. For Texans it is simply the basis upon which the State economy was built post-Civil War and to this day the Longhorn remains a treasured Texas icon.

Below is a stock image of Longhorns. Not my picture.

Yet where did the Longhorn come from? With its long horns it looks nothing like the European cattle breeds. And as any Longhorn rancher knows, it acts differently. The Longhorn is smarter, heartier, can better find forage and water, and is more disease resistant than other popular cattle breeds.

Origin and History of the Texas Longhorn

According to Dr. David Hillis, author of Armadillos To Ziziphus and the Director of the Biodiversity Center at the University of Texas at Austin, cattle likely arose from aurochs about 10,000 years ago and in two different parts of Eurasia; one being in the Middle East, and the second in the subcontinent of India. From there domesticated cattle spread to Africa and eventually via the Moorish invasion to Spain.

Christopher Columbus, on his second voyage to the New World in 1793 and intending to establish a colony in Hispaniola, stopped by the Canary Islands where he purchased pregnant heifers. The cattle thrived in Hispaniola. By the early 1500s the Spanish explorers took descendants from these original cattle to Veracruz on the Gulf Coast. As the Spanish explored Mexico, they took along cattle for food, but many animals escaped or were released into the wild.

The countryside at the time had large and dangerous predators including bears, coyotes, and mountain lions. In an evolutionary act that warms this prior college zoology major’s heart, the strongest feral cattle with the longer horns survived better and bred. Over many generations of survivors and through the process of natural selection, the sturdy, fiercely protective Longhorn that we now recognize came into its own. With its longer horns it was able to defend its calves from predators, fight for dominance in the herd, survive in the wild and even flourish. Eventually vast herds of Longhorn cattle roamed what became in 1836 the the independent country of Texas and later in 1845, the State of Texas. Literally millions of feral Longhorns roamed the broad prairies of the State of Texas.

In the 1870s and 1880s vast cattle roundups and cattle drives began in south Texas, passed through the Texas Hill Country said to be the greatest cattle raising area in the world, and on through Texas and Oklahoma to the railroad depots in Kansas. The Great Western Trail saw at least two million Longhorns arriving in Kansas from where they were transported east to feed a hungry nation and to supply tallow for candles, the primary source for light at night.

Along with establishing the economy of an impoverished State, this era introduced Cowboy culture and the era often portrayed by the westerns in cinema. This author’s great grandfather, Thaddeus (Thad) Septimus Hutton worked as a cowboy and lived near Seymour, Texas alongside the Great Western Trail. It is likely that Thad Hutton in addition to working on a ranch, also rode up the trail to Dodge City where he would have interacted with the likes of Wild Bill Hitchcock, Doc Holiday, Wyatt Earp and other notable Dodge City legends.

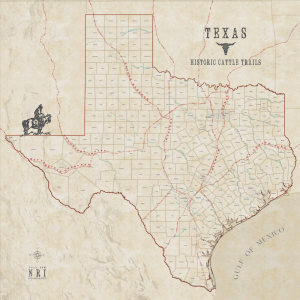

Below are the Legendary Texas Cattle Drives

By the 1900s Longhorns were deemed less desirable than the European breeds that yielded more beef per animal. The era of the Longhorn had passed into history and the Longhorn came close to extinction. The western writer, J. Frank Dobie along with the oilman, Sid Richardson and various nostalgic ranchers began to preserve the breed. Charles Schreiner III, a Hill Country rancher, is best known locally for his great efforts in preserving the Longhorn breed. In 1941 a State herd of Longhorns was established and now reside both in various State parks and on private ranches.

It seemed only appropriate that the first cattle we brought to our Medicine Spirit ranch were Longhorns. The lone survivor now serves principally as pasture art whereas the calves from Black Baldys (a specific mixture of Angus and Hereford) crossed with Charolais are more prized by market forces and are the principal stock on our ranch.

Why We Love Longhorns

Longhorns in addition to their distinctive long horns also are remarkable for their coloration. No other breed has as many different colors as Longhorns including white, brindled blacks and reds, multi-colored roans, yellow linebacks, or everything in between.

J. Frank Dobie wrote in his book, The Longhorns, “Next to the horns…the most striking quality in appearance of the Texas cattle was their coloration. It is incorrect to say that they represented all the colors of the rainbow. Their colors were more varied than those of the rainbow.”

Texas Longhorns look different from other breeds and act differently as well. They possess a sense of pride with their heads held high and the males even demonstrate a swagger. They possess a wiliness not often associated with bovines. The calves are small at birth but grow rapidly. Their muscles strengthen, and they show a sense of of self-confidence not often observed in other breeds. Despite their long horns, the Longhorns are typically gentle. We often hand have fed our Longhorns, something not often possible with many of our Black Baldys.

The Longhorns are easy breeding due to having a larger pelvic outlet than other cattle breeds. Often first time heifers of other breeds are bred with a Longhorn bull because of this easy calving trait received from the Longhorn bull. Longhorns in our experience become the alpha cow in a mixed herd and have a distinct knack for leading the herd to a water source and to the best grazing. In addition to their smarts, the Longhorns are largely disease resistant, saving on vet bills.

In Conclusion

In tribute to this Texas icon, the Longhorn occupies a warm spot in the hearts of Texans. The horns from our first Longhorn now hang proudly in my study where I admire and recall her long life and many feats. Her name was Bell Pepper, and her daughter was named Cinnamon. The thought behind the names was that they “spiced up” our ranch. Indeed they did along with bringing with them a strong sense of proud Texas nostalgia.