This is the fourth blog piece in a series that features our first Border collie, Bandit, and is taken from an unpublished book titled The Bandit’s Gift. I wrote this manuscript which I suppose could be considered my practice book, shortly after retiring from my Neurology practice in Lubbock and moving to our ranch outside of Fredericksburg, Texas. The title of the book hints at our Bandit dog’s substantial role in bringing about our early retirement. Trudy and I feel indebted to Bandit for his efforts in hastening our move from a frenetic life in the city to the beauty and peacefulness of the Texas Hill Country.

This installment describes our migration from Lubbock to our ranch near Fredericksburg. It also introduces Mollie, a female Border collie, whom we acquired shortly before our move to the ranch. Mollie as a puppy came from a New Mexico ranch whereas Bandit had been raised a city dog in Lubbock.

Mollie our second Border collie who was from herding stock

Mollie our second Border collie who was from herding stock

In August of 2001, Trudy and I departed Lubbock for permanent retirement at our Fredericksburg ranch. Bandit and Mollie rode in the backseat nestled among hanging clothes and piles of shoes. Mollie sat on the passenger’s side, Bandit on the driver’s side. As Lubbock receded into the tabletop-flat landscape, Bandit cast what I considered a satisfied if not smug glance out the window for having brought about this major change in our lives. I wondered how our canine conniver felt, as he had been a motivating force for my early retirement, mounting a determined campaign having nearly destroyed our home in Lubbock.

“Bandit, say good-bye to Lubbock.”

His long white tipped tail began slapping the back of the seat.

“Thump, thump, thump.”

“Trudy, that dog sounds like he’s beating a drum, am I imagining it or is Bandit celebrating?”

“Thump, thump, thump.”

Bandit looking so innocent

Bandit looking so innocent

Mollie sat quietly in her corner of the backseat. When I turned to scratch her chin, I noticed her peculiar smile. When Mollie smiled, she retracted her lips and exposed her teeth. Her eyes squinted and her face showed a broad dog smile- a smile sometimes misinterpreted as a snarl. I sensed that Mollie was happy, knowing we were leaving a city and headed permanently for a ranch.

Optimism and a sense of unburdening welled up within me. My exhausted spirit for years had yearned for a saner, more private existence. The long work hours, the stress of holding together a clinic and hospital practice, and the daily grind of dealing with desperately ill patients had extracted a physical and emotional toll from me.

While Trudy and I had worked well together, our communication styles differed. For me, small talk has always proved difficult. Give me a family with a brain-dead member, or the need to relate a terminal diagnosis, and I am at my rhetorical and sympathetic best. But when at a social function calling for light banter, I feel like a stammering dolt. Moreover, I suffer near stupefaction when faced with the usual social banalities.

Trudy on the other hand handles social situations with aplomb. She can discuss grandchildren, the weather, the latest gossip, or pop-culture with the best of them. She finds difficulty, though, when talking of emotionally laden topics, especially those affecting her or her family. It was just such heavy topics that had for years nagged at the corners of my mind.

Trudy’s unhappiness and worry may have prompted verbal zingers aimed at a workaholic, slow to mobilize, and frequently absent husband.

“Remember that Surgeon in Medical Records, draped over his pile of charts like a bad suit of clothes, dead as Hamlet’s buddy, Yorik? You’re not indestructible either Buster. I’m too young and gorgeous to be a widow. Lots of young bucks have the hots for well off, sexy widows.”

“Yeah, rave on,” I had said, suspecting I had not deflected this conversation for long.

Later as I drove off the cap rock of the Llano Estacado and away from the loneliness of the high plains, I became lost in a tumble of conflicting questions and emotions. Long drives have always put me in pensive moods, providing uninterrupted time for contemplation. Memories began to tug at my sleeve.

Being a physician had been at the core of my identity. I wondered how life would change without Medicine being my magnetic north.

Why am I ambivalent about leaving? Sure, I’ve loved Medicine- the intimacy that goes with caring for others. Where’s the satisfaction gone? Had it been the hospital’s economic realities that at times impinged on the quality of clinical care I wished to give? Had this led to incessant medical upheavals? Why had it been a struggle to maintain a successful group practice, run an efficient medical practice, and carry out good clinical care and research? Had I asked too much of myself as both a private practitioner and an academic?

After an initial scuffle in the backseat when Mollie tried to take Bandit’s usual place, the canines had calmed. Bandit circled and plopped down with an audible exhalation. Long before we reached the cap rock, Bandit had fallen fast asleep. Mollie rested her chin at the window and observed passing fence posts, her light blue eyes tracking and flicking from one to the next.

Bandit on the left and Mollie on the right in profile

Bandit on the left and Mollie on the right in profile

As the miles sped by, my mind shifted from labors left behind to this land’s history through which we passed which I began to recall. We headed southeast, counter to the migration of earlier settlers, toward what in 1800 had been the northernmost frontier of the Mexican State of Coahuila and Tejas. Long before becoming a Mexican State, the land had been occupied by Tonkawa Indians who in turn gave way to the more warlike Apache, Kiowa, and Comanche.

Texas won its independence from Mexico in 1836 and became an independent republic. In 1845 a proud but destitute Texas joined the United States of America as its 28th State. The following year German immigrants arrived in the Hill Country to partake of free land and increased economic opportunities.

In Germany, the unwitting emigrants had been reassured the new land was peaceful, only on arrival to find themselves in their newly established village, surrounded by hostile Native Americans. This grievous case of real estate exaggeration ranks just behind Eric the Red who named a frozen expanse of icecap, Greenland.

We traveled through Sweetwater, a small west Texas agricultural town with yet another unpretentious name. I thought- did no one have imagination when giving names?!

Bandit briefly awoke when we stopped at a red light in Sweetwater. I felt his cold nose nudging my shoulder, urging my attention. I reached back and scratched his ears. The white tip of his tail (the so-called Shepherd’s Lantern) striking the back of my seat.

“Thump, thump, thump.”

Mollie glanced at her emotionally needy canine companion but quickly returned to watching the towns stream by. I wondered if Mollie expected a meandering herd of sheep or scattered herd of cattle to appear in desperate need of a Border collie to organize them.

I thought how different these two dogs were in soliciting affection. Bandit fawned on people, begging- even demanding attention. Mollie never stooped to such antics, although she appreciated affection when it was offered by a family member.

Mollie was a rare Border who loved to swim

After leaving the town behind, I heard Bandit again flop down in the back seat. My own thoughts returned to the history of central Texas that still lay several hundred miles ahead.

German men from Fredericksburg led by their able leader John Meusebach, in a desperate gambit, ventured out of the relative safety of their new settlement to secure peace with the natives. They successfully met up and powwowed for several weeks beside the San Saba River. After much talk, countless pipes, and no doubt many earnest, silent German prayers, a peace treaty was established with seven large tribes of natives.

This treaty, remarkably, over the years has remained intact. It is claimed to have been the only treaty in Texas, and possibly the entire United States, with Native Americans to have not been broken. An annual Powwow of Native Americans and Fredericksburg citizens celebrated the success of the treaty for many years thereafter in Fredericksburg.

While the peace talks had dragged on alongside the San Saba River, other natives surrounded the village of Fredericksburg, awaiting news that would either prompt an attack on or befriend the hapless settlers. Huddled within their makeshift cabins, stoic German settlers tried to carry on their lives without projecting fear to their children.

On Easter eve night, bon fires ominously appeared on the many hills surrounding Fredericksburg. The German settlers worried these fires might signal an impending attack. In truth the bon fires communicated to the Native Americans high in the hills around Fredericksburg that a peace treaty had been achieved at the Powwow on the San Saba River.

Initially the significance of the bon fires was unknown to the settlers, but the fires on Easter evening prompted one mother, full of bravado, to proclaim to her worried children that the Easter Bunny was building fires to boil their Easter eggs. The brave spirit manifested by the unknown German mother inspired for many years the yearly Fredericksburg Easter fires tradition where bon fires were built each Easter eve on top of the hills surrounding Fredericksburg.

We motored across the Texas prairie where 150 years earlier the Apache had been driven by the still fiercer Comanche. I recalled the struggle for control of the green hills and streams of central Texas. With increasing distance from Lubbock, the table-flat, featureless, and bleak landscape gradually changed into rolling prairie dotted with tall prairie grasses, scraggly mesquite, cottonwood, and Juniper trees.

We traveled through Coleman to Santa Anna (named after a famous Penateka Comanche chief) where we turned south, passing by the ruts of the old Great Western Cattle Trail. A roadside historical sign informed that more cattle had passed up this cattle trail to Kansas than had occurred on any of the other Texas cattle trails. The Western Cattle Trail ended in the wild western town of Dodge City where lawmen Bat Masterson and Wyatt Earp became famous and where Earp was finally laid to rest.

Some twenty million Longhorns had moved up the cattle trails following the Civil War, establishing a viable economy for a desperately poor Texas. I proudly recalled my great grandfather, Thaddeus Septimus Hutton, having been a Texas cowboy who had likely pushed cattle up this very trail through the Oklahoma territory to the rail head at Dodge City. I pondered what it must have been like to herd cattle in the 1870s through wild country. Had he even a glimmer of the historic nature of the western life he lived and the fame that would be later accorded the lawmen of Dodge City. Of one conclusion I felt certain, that more hard work and less adventure had existed on the cattle trail than was depicted later by Hollywood movies.

Several hours further on, the rolling prairie gave way to green hills, clumps of stately live oak trees, and cultivated green pastures. Artesian spring fed streams and rivers snaked among the hills. Wild game had been and remains prevalent, and the tall native grasses supported greater numbers of grazing animals than had the near barren Llano Estacado.

Looking at this dramatic transition in the land helped me to understand why the Native Americans believed the Hill Country possessed such “strong medicine.” The Texas Hill Country with its beauty and bounty favorably compares to the western, more arid portion of the State. I thought no wonder Native Americans had fought so ferociously to maintain control of the Hill Country.

While I mulled these matters, Mollie, with remarkably sustained attention, continued to observe the changing landscape. Once when passing an eighteen-wheeler, Mollie stood upright, staring at a black, ride along dog that stared back from the truck’s passenger window. I could see the other dog barking. Mollie calmly observed the dog and gazed at the truck until it was lost to sight.

Bandit didn’t awake again until we arrived in Brady, the geographical center of Texas. He awoke, stretched, yawned, and appeared to anticipate our arrival at the ranch. I felt his chin on the back of my seat and sensed his warm, moist breath. I could see in the rear view mirror that he had perked up his ears and was staring down the highway ahead of us. When I reached to give Bandit a scratch, I was rewarded with several languid licks to the back of my hand.

Mollie and Buddy at the ranch

“Thump, thump, thump.”

An hour and fifteen minutes later, we drove through the front gate of our ranch. I halted the car briefly, so that Trudy and I could exhale years of pent up tension. Whimpers came from the backseat. Trudy and I opened the back doors of the car. Mollie leaped out and sped across the pasture, ears flattened to her head, back arching, and legs striding. Bandit jumped out and loped behind Mollie, inspecting trees, clumps of grass, and rocks. Mollie scared up a jackrabbit, and both collies began a deliriously happy, zigzagging pursuit, interrupted only finally by an impassable barbed wire fence.

Trudy and I joined hands and watched in peaceful silence; an interlude as pure as that between young lovers. We had parked on a caliche ranch road near a grove of live oak trees. We wordlessly observed the rabbit chase and basked in the exuberance of the moment. Bandit and Mollie eventually strutted back to the car; tails held high. The two dogs sniffed and scuffled and seemed to be thoroughly enjoying themselves.

From over my shoulder, an orange-red sunset beckoned above a white limestone ridge. We heard the mellifluous sounds of water rushing over stones in a nearby brook. I experienced a rare moment of awareness and understanding. What had seemed confused a few hours earlier, in this tranquil setting, now seemed clearer, even achievable. I could feel a smile develop across my face.

“Welcome home Trudy.”

Trudy slowly turned her eyes to meet mine. I saw a loving smile, crinkled nose, and teary eyes.

“Didn’t think I’d get you out of Lubbock alive,” Trudy said with an uncharacteristic tremor in her voice. Moments later her tendency to chide rallied and she said, “Besides Cowboy, why are you planted here like a stupid yucca, let’s get on with our new lives!”

Just as I leaned across the front seat of the car to kiss Trudy, from the backseat came Bandit’s black and white head. Trudy and I stopped just short of planting bookend kisses on his furry snout. Trudy and I laughed, and Bandit cocked his head impishly as if understanding the joke. Trudy and I were now retired, and with Bandit and Mollie, we were four.

to be continued

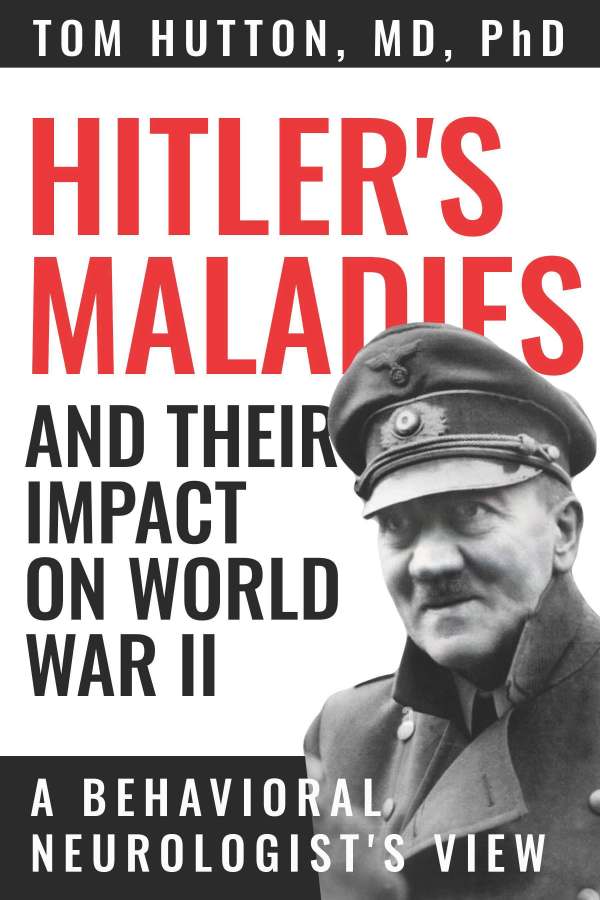

If you have not had the chance to read my latest book, Hitler’s Maladies and Their Impact on World War II: A Behavioral Neurologist’s View (Texas Tech University Press), I invite you to do so. The book explores an important aspect of the Hitler story and World War II that has not been well studied. Many of Hitler’s catastrophic errors including the premature invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941, the slowness of German forces to counterattack at the Battle of Normandy in 1944, and the highly risky Battle of the Bulge in late 1944 into 1945, can be better understood, knowing the sizeable impact that Hitler’s physical and mental conditions had on these vital battles.

Also, consider picking up a copy of my earlier book, Carrying The Black Bag: A Neurologist’s Bedside Tales (Texas Tech University Press). Please join me on my personal journey as a physician and meet my patients whose reservoirs of courage, perseverance, and struggles to achieve balance for their disrupted lives provide the foundation for this book. But step closely, as often they speak with low and muffled voices, but voices that nonetheless ring loudly with humanity, love, and most of all, courage.