While folks are generally well acquainted with stories about their parents and typically have a reasonable number of stories regarding their grandparents, stories about great grandparents are often extremely limited. Knowing more about my great-grandfather, Thaddeus Septimus Hutton, the first Hutton in Texas and a rancher, would be most welcome. The following blog piece shares what we know about Thad’s time in Texas and what might have happened based on the historical happenings surrounding him. This piece might also be viewed as a not too subtle plea to document family stories for future generations, as they can easily become lost in the mist of history.

Following my retirement from medicine, Trudy and I began researching our family’s genealogy. We wrote “Our Family’s History: The Huttons” and shared our findings and write up with my siblings. When it came to Thaddeus Septimus Hutton, fortunately my father had written a short article for a school assignment about his grandfather Thad Hutton. Dad’s theme provided valuable information. I learned that as a boy Thad, as he was called then, grew up on an estate in northern Virginia ( called Huntingdon). It was said to be almost in the shadow of the Capitol. Thad experienced the drama of the Civil War unfolding around him. Five battles were fought nearby his home. Fortunately, Thad was not directly involved in the war being too young to enlist or else our line of Huttons might never have occurred. Following the war and upon achieving the age of twenty one, he joined several of his brothers and sisters who had already fled the federal zone in Virginia to move to a more promising area along the Kansas and Missouri state line. There they had sought better opportunities and lives.

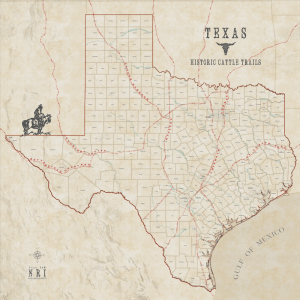

Thad lived in Missouri until 1875 before striking out for Texas. He traveled by covered wagon to Palo Pinto County and lived two to three miles north of the small town of Gordon (west of Fort Worth) and at that time it was located on the frontier. He married Elizabeth (Betty) Ragan on October 31, 1876 when an itinerant preacher of the Gospel of Christ denomination happened by to perform the marriage ceremony. Had Betty accompanied Thad in the covered wagon? We’ll likely never know. Betty had lived close to Kansas City and not far from Thad Hutton’s home in Missouri, suggesting they had likely met in the vicinity of Kansas City. She was a diminutive Irish lass who reportedly possessed a sharp tongue and later demonstrated fecundity as shown by birthing six children, one of whom died in infancy.

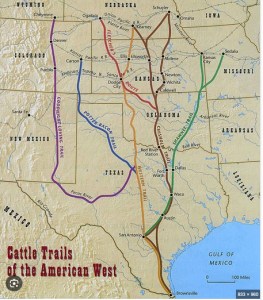

Betty gave birth to their first child, Thaddeus Leslie in 1878 while living near Gordon, Texas. On Leslie’s birth certificate, Thad’s occupation was listed as “cowboy.” Not long after Leslie’s birth, Thad and Betty pulled up stakes and moved further west to live near Seymour, Texas. No clear reason is known for this move, but a strong suggestion exists with the Great Western Trail (GWT) running through Seymour. The trail began in South Texas and traveled north to Dodge City, Kansas. Thad was associated with the P8 Ranch near Seymour that must have. been very close to the GWT. The P8 ranch apparently no longer exists.

From here on Thad’s story of ranching in Texas becomes more speculative. The family Bible reveals that Thad ranched cattle in Jack, King, and Knox counties, all counties close by Baylor County where Thad, Betty, and their growing family resided. Did Thad herd cattle up the Great Western Trail to Dodge City? This famous western cow town served as a major railroad terminus for moving cattle to eastern markets? Might Thad have interacted in Dodge City with famous western law men and gunfighters such as Wild Bill Hickok, Bat Masterson, and Wyatt Earp, all of whom established their reputations in Dodge City? Did he rest up from the cattle drive in Dodge City, said to the most wicked city in the country and home to the Long Branch Saloon and China Doll Brothel? Unfortunately, the answers to these questions, we will likely never know.

We may add to our understanding of Thad Hutton by examining the historical happenings that occurred around Seymour around the time Thad lived there and speculate on their impact on him. Settlement in what became Baylor County (Seymour becoming the County seat in 1879) was not possible until the U.S. Army in 1874 and 1875 defeated the Comanche, Kiowa, Southern Cheyenne, and Southern Arapaho tribes and removed the native Americans to Oklahoma reservations. This war occurred when the U.S. Army declined to enforce the terms of the earlier Medicine Lodge Treaty that forbid white settlement on Native American land. This conflict known as Red River war had ended only a few years prior to Thad and Betty moving to the area.

Information from Lawrence L. Graves describes Baylor County as follows: “This was the era of free-grass ranches, a time in which farmers and ranchers sometimes violently contested for land. Settlers from Oregon, led by Col. J. R. McClain, moved to the site of Seymour in 1876, for example, but were driven off when cowboys ran cattle over their corn. In 1879 the Millett brothers—Eugene C., Alonzo, and Hiram—came from Guadalupe County to begin ranching in Baylor County. They ran a tough outfit and used their armed cowhands to intimidate would-be settlers and the citizens of newly founded Seymour. Violence and contention plagued the county during the first years of settlement. Baylor County’s first two county attorneys were forced to resign, and in June 1879 county judge E. R. Morris was shot and killed by saloon keeper Will Taylor. Later the Texas Rangers gradually brought peace.”

How were Thad and Betty affected by the ongoing violence? The Texas of legend was predicated on open land and access to water sources. With barbed wire having been introduced in 1875, the cattle drive itself, an integral part of the Texas legend and the basis for the Texas economy, became threatened. With Thad being a rancher was he involved in the range war? Did he cut barbed wire to move his cattle among the counties in which he ranched or was Thad a mere observer to the drama unfolding around him. Answers to questions such as these, we’ll never know.

With public support fence cutting became a crusade that led to a Fence Cutting War. Rabid anti-monopoly sentiments arose across Texas with fence building viewed as monopolistic and infringing on the rights of small ranchers and farmers. Saboteurs cut fences and left threatening notes for fence builders. This conflict between free range ranchers and farmers would have likely continued and perhaps escalated further had the reasons for the conflict not been deflated by severe environmental issues.

Again according to Graves, “By 1880, fifty farms and ranches encompassing 13,506 acres had been established in the county (Baylor County), supporting a population of 708 people; more than 13,506 cattle were counted in the county that year.” Among these residents resided Thad, Betty, and son Leslie.

These early settlers including the growing Hutton family were severely tested in 1886 and 1887 by a severe drought. This difficult time for the Hutton family stemmed from range wars and the drought. Incidentally, my grandfather, John Frank Hutton was the last born of that generation in 1888, being born in Garden City, Missouri.

The building of railroads has long been credited with ending the Texas cattle drives and ending an illustrious era. But it was not until 1890 that the populace of Baylor County, home to Thad and Betty Hutton, raised $50,000 to insure completion of the Wichita Valley Railway, linking Seymour to Wichita Falls, 52 miles to the east. The reasons for the departure appear to largely due to closing off the open range, a severe lack of rain, possibly threats of violence, and the inevitable approach of railroads that ended the famous Texas of lore and reduced the need for cowboys such as great-Grandfather Thad Hutton.

If you have not had the chance to read my latest book, Hitler’s Maladies and Their Impact on World War II: A Behavioral Neurologist’s View (Texas Tech University Press), I invite you to do so. The book explores an important aspect of the Hitler story and World War II that has not been well studied. Many of Hitler’s catastrophic errors including the premature invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941, the slowness of German forces to counterattack at the Battle of Normandy in 1944, and the highly risky Battle of the Bulge in late 1944 into 1945, can be better understood, knowing the sizeable impact that Hitler’s physical and mental conditions had on these vital battles.

Also, consider picking up a copy of my earlier book, Carrying The Black Bag: A Neurologist’s Bedside Tales (Texas Tech University Press). Please join me on my personal journey as a physician and meet my patients whose reservoirs of courage, perseverance, and struggles to achieve balance for their disrupted lives provide the foundation for this book. But step closely, as often they speak with low and muffled voices, but voices that nonetheless ring loudly with humanity, love, and most of all, courage.